Subcultures don’t exist in vacuums. Coherent expressions of youth rebellion arise when certain social factors align and coalesce as an adverse reaction to the prevailing culture. They’re manifestations of expression that spread as concentric circles of influence like ripples across water – before they run their course and dissipate. Youth cultures are beautiful in their brief changes of cultural tact that reverberate through art, music, and style. Janette Beckman has dedicated her life to capturing these cultures, from the birth of punk in the Uk, to the emergence of hip-hop in New York, to the LA gang scene of the ’80s. Janette’s body of work is an archive of rebel cultures, often capturing soon-to-be household names in their formative stages. Her images carry a sense of clarity and sincerity that remains long after these cultures wither and disappear.

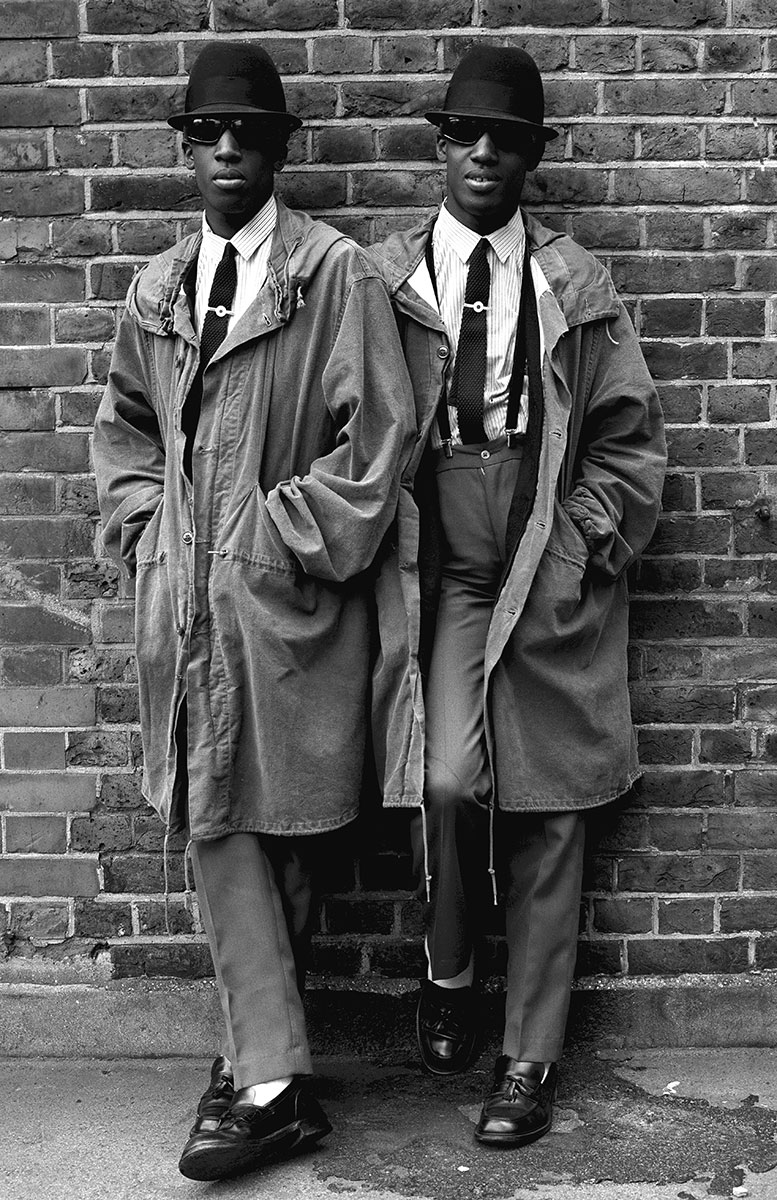

Mod Twins, London, 1979

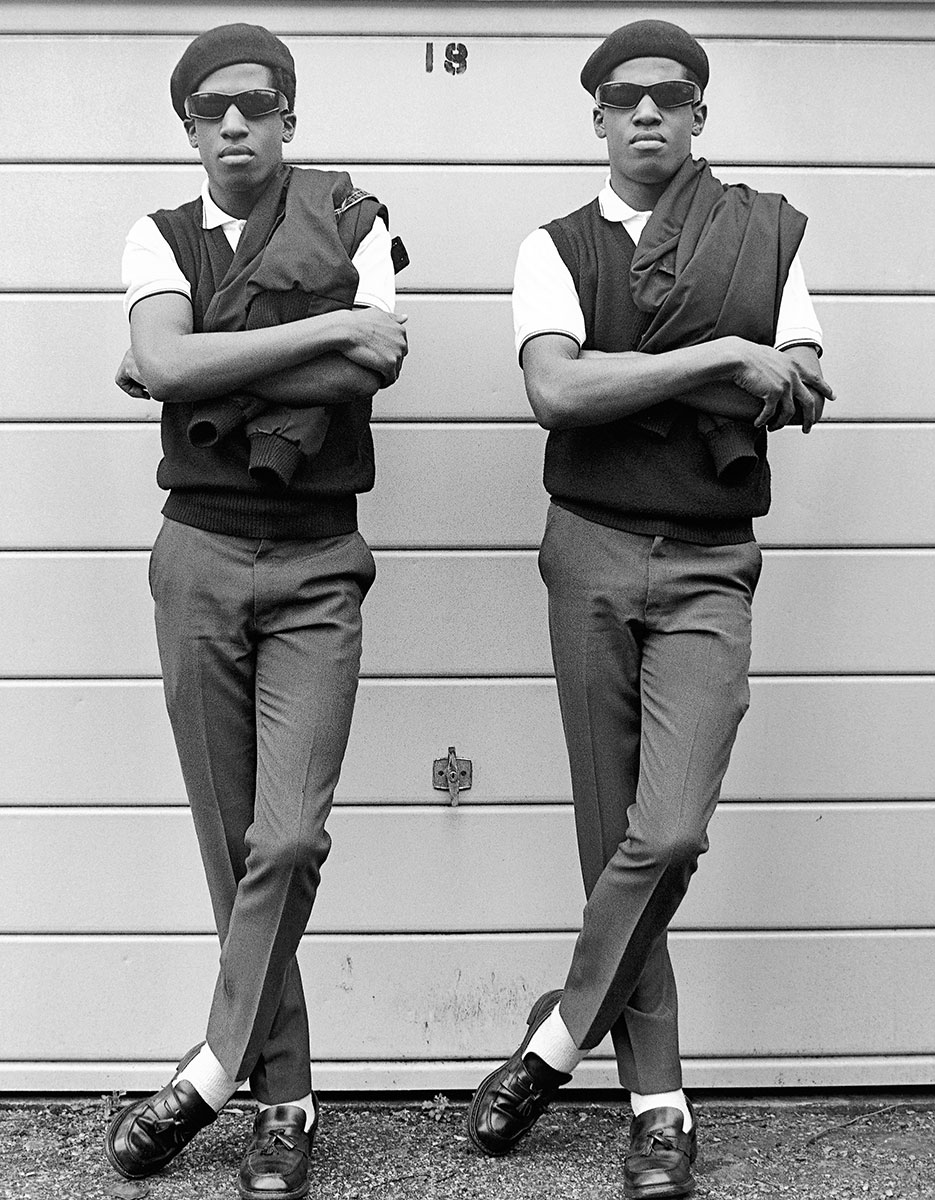

The Islington Twins, London, 1981

You studied at art school from quite a young age.

I was 20 years old when i went to art school. I really wanted to be an artist, but I just wasn’t a good enough drawer. So I was like, “Ah, maybe I will do photography instead.” I studied photography at the London college of Printing. I was there for three years and I was in my rebellious stage. I just went off and did my own work basically. Immediately after I got a teaching job in this little college in North London where there were a lot of punks and squatters. One day I came out at lunchtime and there were these two mod twins, the Islington twins, they were standing in the schoolyard just hanging out. They were at college, but not in my class, and I was like, “Wow, these guys are amazing,” and I took a picture of them. That was one of the first pictures of [that] kind of rebel culture style that I ever took.

What was the cultural climate like in London at the time?

It was very old school in London. The Queen and the country. If you were born in the lower class you’d stay in the lower class. That system was very strong when I was growing up in the late-’50s, early-’60s. Suddenly right around ’76 you started to see kids dressed in punk clothing – mohawks, safety pins, wearing garbage bags. You were just like, “Wow, what is this?” The moment Johnny Rotten said “Fuck” on TV [December 1, 1976] that changed everything – the country just split. it really felt like we could do something different.

Looking back people often refer to a sense of energy or dynamism in the air. Is that a product of nostalgia, or was it really like that?

There was a huge amount of energy, and it wasn’t just punk. It was 2 tone, and ska, and rockabilly, and skinheads, and all sorts of youth rebellion cultures. You saw all these kids at concerts that were really dressed up. It did have a certain rebellious energy to it, and at the same time the music was incredible.

Did you just dive headfirst into it?

One day I walked into this weekly music magazine called Sounds and I said I want to show my portfolio. I met this woman who was the features editor at the time, Vivien Goldman. she was like, “Oh, I like your pictures. Why don’t you go and photograph this band Siouxsie and the Banshees tonight for us?” I’d never photographed a band before in my life. I just put some film in my camera, went and took shots at the Roundhouse. I developed them all overnight in my darkroom, made the prints, and went in the next day. She was like, “These are good. Here’s another band for you.” That’s how I started working in the music business.

How influential was the music press at that time?

Super influential, it was amazing. There were four weekly music mags – Sounds, Melody Maker, Record Mirror, and the NME. We were all in competition. We all came out every week and people read them from cover-to-cover. You could make a band by writing a really good review. People were so obsessed with music, and there was so much going on at the time.

At the time that you were shooting Siouxsie and the Banshees and The Clash and all these bands, did you have a sense of the gravity of what was happening?

Absolutely not. Don’t forget a lot of those bands were just young bands at the time. When I shot the cover for The Police I remember the art director saying, “There’s these three punks, do you want to do their record cover?” People weren’t famous. Celebrity culture didn’t really exist at all. Everybody had their own style. One minute you’re a punk on the street, and the next minute you’re in a band. You didn’t really have to know how to play, you didn’t have to be beautiful. They didn’t have these concepts of classic beauty, you didn’t have to be a six foot tall blonde model-type. Look at Shane MacGowan [The Pogues] – he got completely famous and he hardly had any teeth but he was one of the most iconic guys on the scene. Because he was that good and he had the attitude, and that’s all people cared about.

How important for you was it to document the crowd around the scene, as well as the band?

I loved that, because just doing live [band] pictures wasn’t really my thing. I liked doing all the backstage stuff and the fan stuff. You’d be hanging around waiting for the band and you’d see amazing people coming into the club. That turned out to be actually more interesting for me than photographing the band some of the time.

Do you think those images capture that historical context as well?

Nobody could give a toss about them at the time, except for us – the people that were in the culture. It was the same thing with hip-hop. When I did hip-hop here [in New York] nobody gave a rat’s ass about it. Except for the people who were in it.

You left England for New York in ’82. What prompted that move?

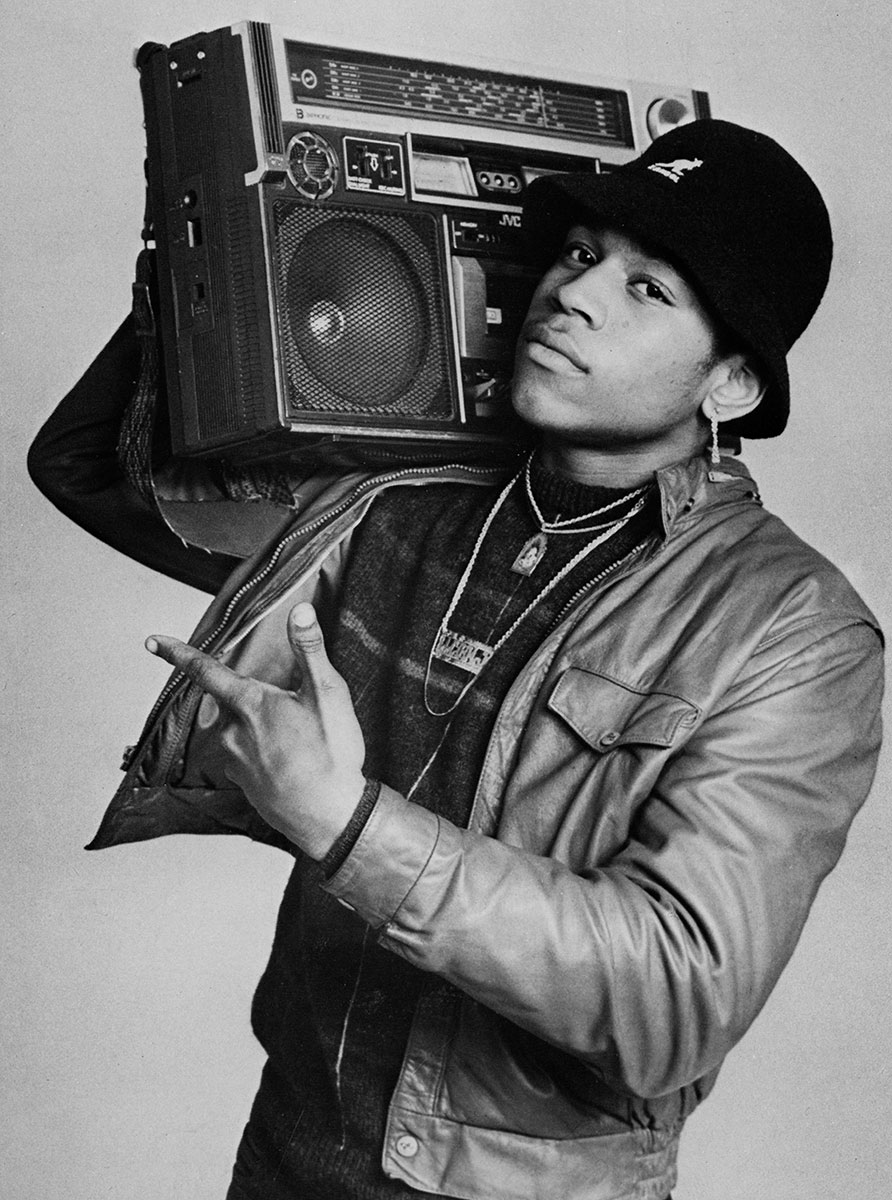

I’d been working for the music press, covering all these youth culture things. Punk was on the wane and the new romantics were in. Everything was changing, around October [or] November of ’82 the first hip-hop show came to London. I went there to cover it for Melody Maker, it was a mind-blowing experience for me – it really changed my life. I’d gone to the hotel and started photographing all these people that were hanging around. It turned out that I was taking pictures of these people that were going to become hip-hop legends. People like Afrika Bambaataa, Grand Mixer D.sT [now known as GrandMixer DxT]. I got Futura and Dondi – two of the greatest graffiti writers ever – tagging a dumpster. It was just so crazy, I didn’t even know who they were, I was just instinctively drawn to them. Coincidentally, that Christmas I was going to visit a friend in New York, and I ended up staying because it was unfolding in front of me. You’d go out of your apartment and get on the train and it’s covered in art, there’s graffiti all over the place. You’d get off the train and there’s a kid breakdancing on some piece of cardboard on the street. It was really amazing. I thought, “Well I photograph music, so I’ll take my portfolio around the American big labels.” I made appointments and went up to the record companies and they were like, “Your work is too gritty. We can’t hire you because you can see spots on people’s faces and their hair doesn’t look right.” But it turned out that all these young, startup record labels needed a photographer. I started working for Next Plateau, Def Jam, sleeping Bag. in the end I became the go-to photographer for this Sleeping Bag label that turned out to have Salt-N- Pepa, EPMD, a huge mass of iconic bands. I was shooting press pictures for Def Jam. I shot slick Rick, I shot the first ever press picture for LL cool J – that picture of him with the boombox on his shoulder. It was kind of like punk, there were a lot of similarities. New York was broke, like how London was broke at the time when punk started.

Slick Rick, New York City, 1987

LL Cool J, 1985

The Clash had been to New York in ’81 and they’d linked up Futura and Grandmaster Flash on that tour. Were you aware of that at the time?

I didn’t know anything about that until later. In fact everybody I know here in New York right now was at that Clash concert. I guess they were all punks and Clash fans back in the day. There was a lot of crossover and they respected me because I photographed bands like The clash and Boy George. They were like, “Oh, you’re cool. You took that picture.” Whereas, the actual mainstream record companies didn’t really care about that. The hip-hop guys definitely knew what was going on in England.

People have argued that the spirit of punk shifted to the hip-hop scene in New York around that time. Is that something you’d agree with?

There are parallels between the cultures for sure, but I don’t think they got it from punk. someone was asking me last week in London, who do I think had more attitude, punk or hip-hop? And I’d probably say hip-hop, because a lot of the punk kids were messing about in a way. The hip-hop guys seemed really like they meant it.

What resonated with you the most when you were shooting? Was there something you were looking for?

To this day I shoot in the same way. I’ve always liked street stuff, because when you’re on the street anything can happen. Like I was taking this picture back in the day of this group, Freshman. They were there on this corner outside a deli on the Lower Eastside with their giant boombox. It’s four o’clock in the afternoon and all these kids come around the corner, just let out from school. So they jump in the picture, and now I’ve got this picture of these two guys with a giant boombox and all these kids doing the hip-hop thing. It’s a great picture that you could never have posed.

How did you approach things? sometimes you’re working in a documentary capacity, sometimes you’re working for clients, sometimes you’re working for the labels – does it all feed into each other?

People like my kind of naturalistic style. I don’t like posing people, if I go to photograph someone I will move them if the lighting is better – but I like people to pose themselves. if I have to photograph a musician, I’ll be like “Where do you live?” I’d much rather do it somewhere that means something to somebody. I often have people come to the studio and we’ll walk around the corner and see something. It’ll be like, “How do you like that doorway? Okay, let’s do that.” I’m not very technical, I’d rather not have an assistant when I work. I’d rather just walk around with a person and talk, because it’s a collaboration between you and the subject.

Do you try and stay objective? It seems like you’re quite involved with the people you’re shooting.

It’s a conversation, and I’m quite chatty so it’s hard not to get involved. You spend a day with somebody and you’re talking with them and they’re telling you about their boyfriend or something, oh boy. You can’t help but be involved on a human level. Life is all about relationships.

Can you tell me about your role with Jocks and Nerds?

Marcus, the editor in chief, contacted me after the first issue came out. I got this mysterious email from someone going, “Hi, i like your work. Do you want to work for my magazine?” He sent me [a copy] and I thought, “Oh this is a really cool magazine.” It’s the nicest I’d seen since The Face. I’ve been working for them ever since, it’s quarterly and I’m now the New York editor – which is great. I can suggest stories to them, i go “Oh I want to go shoot Harlem in Easter.” it allows me to shoot things that I want to shoot, and they normally run them.

What was it like to re-enter the print world?

Well the magazine is a quarterly, so you don’t have to hustle so much. I’m a print person – I really like magazines, especially ones that are really well produced. If i didn’t like a magazine I wouldn’t work for it.

Which memories stayed with you? Was it those iconic scenes, or the smaller periphery street side images?

I don’t really differentiate. So called ‘iconic’ images, there’s some that are my favourites – I think [they] are some of the best photos I ever took. But I still like really obscure ones, and now people are looking at those and going “Oh, these are really amazing.” Like a picture of four kids standing outside that shop, Boy, on kings Road. People are starting to love that picture. Sometimes I think “Am I going to have to wait 30 years for somebody to look at something I shot for Jocks and Nerds and go ‘Oh, that’s iconic’?”