Hau Latukefu is an OG in every sense of the word. From speaking his unique truths as part of hip-hop duo, Koolism in the early 90s-00s, to firmly having his finger on the pulse of Australia’s budding hip hop and rap scene, hosting triple J’s Hip Hop Show, to using his experience to uplift exciting talent through his label Forever Ever Records, his resume is unmatched.

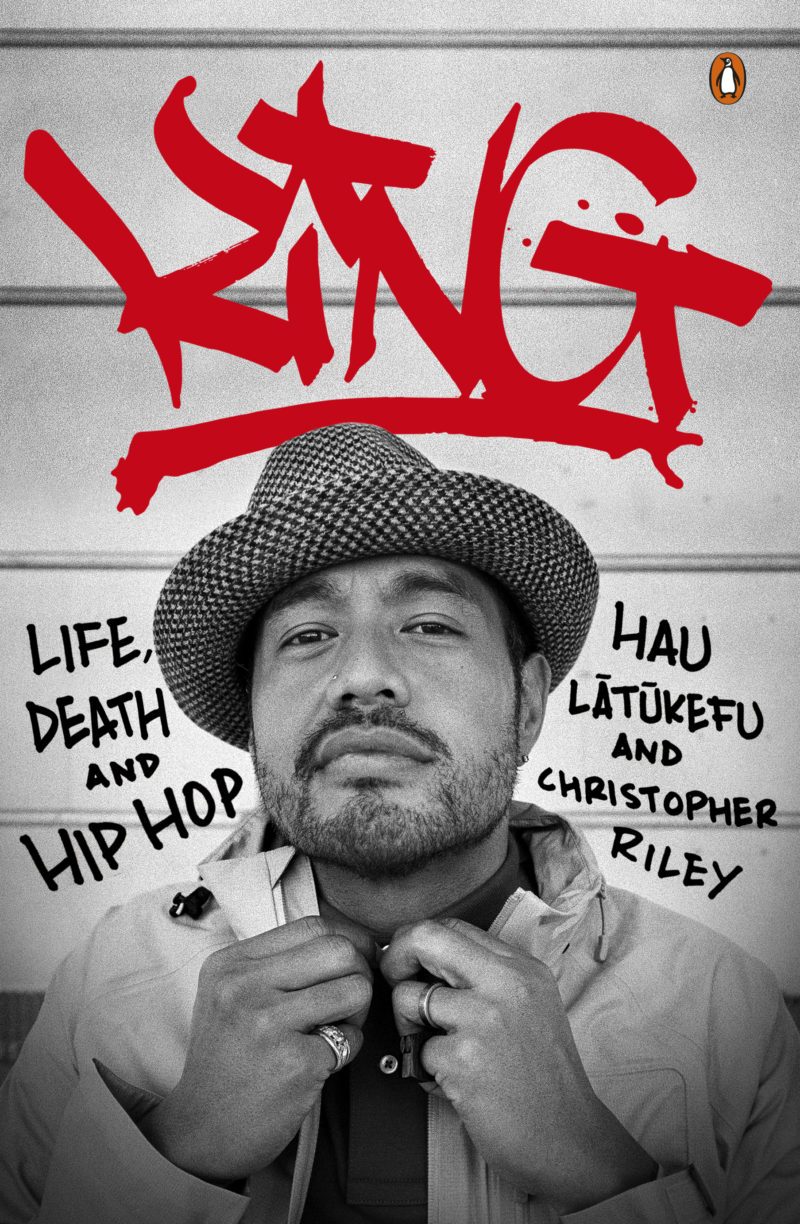

From humble beginnings in the south-east NSW town of Queanbeyan, to the bustling melting pot that is Sydney, Hau’s love for music, community and culture is richer than any person could obtain in wealth. Dedicating much of his career to authenticating an Australian hip-hop sound, Hau has been a guiding light and a source of counsel and inspiration for acts like Onefour, Becca Hatch, Hoodzy and CG Fez. Having recently hung up the mic at triple J after 14 years on air, his expertise and voice is still one that echoes through the halls of many studios and creative spaces today. Most recently, with the assistance of co-author Chris Riley, Hau has been able to reflect on his life in his memoir KING: Life, Death & Hip Hop. A family man, a music lover and a proud advocate for the underdog, we chatted to Hau to reminisce on the years gone by, and discuss his memoir in detail.

Congratulations on the release of your book KING: Life, Death & Hip Hop, it must feel incredibly surreal to have something so personal like a memoir out there in the world for people to read.

It is very surreal. Even when Chris Riley, the co-author, approached me, he approached me with the idea of a book on the history of hip hop in Australia and he said, “Have you ever thought about that?” and I said, “Yeah, I actually have.”, then he asked if I’ve ever thought about writing a story of my life, and I said, “No, no, no,”. If you know me, I just like to kind of keep my head down and work, and let my work and music speak for itself. So the thought of me telling people what I’ve done, I was never really confident. I think it’s just my upbringing, raised to be humble. And I thought, I don’t know, is my life that interesting? And he said, “Yeah, it’s really interesting.”. Because Both he and my wife told me that the reason I don’t think it’s very interesting is because it’s my life. But to someone on the outside, it is quite an extraordinary life. So I thought yeah, okay, let’s do it. Then there’s the whole process of talking about everything, and through that, you kind of realise, oh, wow, okay, yeah, I did this stuff. And so I’m thankful that we did write it. And now it’s documented not only for me, but my family as well.

Yeah, it’s something tangible that generations forward can hold on to and keep as something sacred.

Yeah, definitely. Something tangible, something physical that you can have. I know with the generations gone by, things are all digital. But things that you can actually still hold and you can look at and put somewhere still means a lot. And the same with records, we can listen to mp3 all day, but when we have a vinyl in our hands, looking at it, putting it on the record player and playing it, it’s a whole different feeling. So having the book there and feeling like my kids, even my grandkids will be able to pick it up. It’s a special feeling.

What was the first thing that you remember writing down for the book?

It must have been the title, ‘King’. My name Hau translates to “king” in Tongan, ‘Hau’ means the helper or the supporter. And when we were thinking about titles, I was thinking about old song titles I had. Then my wife said, “What about ‘King””, I was like, no way [laughs]. You know, people can call you king, but you can’t call yourself king. And that’s the one thing I didn’t want people to see, but I think it’s part of the upbringing where we don’t get to really, like, big up ourselves without fear of being ridiculed. But my wife was like, this is not the time to be humble, this is the time to speak about you, your life, family, achievements – be proud. So yeah, ‘King’ was the first thing I wrote. Obviously, to do with my name, but then there’s also that being a senior figure in the hip hop community, as well as having the power and platform to be able to develop the next kings and queens.

You touch on your origins growing up in Queanbeyan in your book, tell me a little bit about your experiences there? I understand it’s kind of rural and city at the same time.

I used to call it a country town with city benefits. Back in the day, it used to be called struggle town. You know, it’s funny, Mounty (Mount Druitt) reminded me a lot of it. But yeah, it’s hard to say. Because it’s on the ACT border, it does feel like it’s part of Canberra. It was that kind of weird mix of old town New South Wales, but we’re right next to Canbera, which is a city. But people in Canberra used to look down at us like we’re some kind of poverty stricken place, but it was a bit rough. Back then in the 70s and 80s, it was very quiet, with a small Tongan community, but very tight knit.

Did you have any unique experiences being there as a Pacific Islander?

I was very fortunate that my father moved with his brothers. My mum had brothers there as well, so we have a lot of cousins there. That was our weekends, spending time with the family. I was very fortunate to have that. And then outside of that, there was a smaller community. And back then everyone knew everyone. Even other Pacific Islander communities were there, we’d all be close together. Because we were all we had. So it was quite unique. It was a beautiful time. But obviously, there was racism, bigotry and things like that. But that kind of built character.

When was your first brush with hip hop music? When did you know that you wanted to make music?

I have an older sister and have a lot of older cousins. And as a young person, you follow everything they do. They’d listen to a lot of reggae, r&b, and soul. And then when we started seeing hip hop, which was very rare back then, you’d see it sometimes on Rage or other TV programmes, it was like, “What is this?”. It was very different and it looked dangerous, very kind of anti-establishment, and that was the music for our generation. We latched on to it, you know, and we saw black and brown kids, and felt a kind of kinship. Being here in Australia, the only representation that we saw was in football, and even back then, there were probably one or two or three players that were Islanders. It was either that, or getting arrested on TV. So even though they weren’t Pacific Islanders, they had that skin tone that we felt some kind of connection or relationship to. Then it turned into breakdancing, and once I hit high school, that’s when I said I’m gonna be a rapper.

What was your parents reaction at the time to you wanting to pursue music?

Fortunately, my parents supported everything that I wanted to do. I was a good kid as well. My older sister, she walked so I could run. Knowing the kind of family dynamic with girls being a lot more restricted than the boys, she was she was quite rebellious. Understandably so. Whereas I was just at home or concentrating on rugby. So I never had any problems with my parents. They loved my friends. My friends loved them. They had always been there. I used to work at the Casino in Canberra, and when I quit, that’s when they were like, okay, make sure to have a plan B. Which I can appreciate at the time, but sometimes what you need is stubborness, and that selfishness. When you’re fixated on what you want to do, you have tunnel vision on trying to be who you wanna be. So when I started doing shows and people started coming to them, my parents got to see it all. So yeah, I’m very fortunate that they were along for the ride and never once tried to do the whole “we didn’t come from Tonga for you to be a rapper” thing, so yeah, very thankful.

I’m sure you also integrate the way that you were raised into the way that you’re raising your kids now. Especially with your love for hip hop, I’m sure you do a big part in passing on music and life knowledge to them in that way.

Yeah, definitely.Music played a big part in my family life. My Dad would play Tongan music in the house, and also loved country. And that’s what it’s like now, when I get up and am fixing the kids lunch or breakfast, we have our own little family playlist. My daughter loves BlackPink, my wife loves musicals, my son loves Headie One, Central Cee, Onefour. For me in the morning, I’ll play reggae, dancehall. When I’m cooking dinner, it’s jazz, soul, to try and mix it up. The kids really love it, and it’s awesome to see them try and talk to their friends about music. Sometimes, when my son talks about music and lyrics, I’m like, “Oh, wow. Do you really think about it?”. Then he tries to have those conversations with his friends and they’re like “I don’t know, I just like the beat.” [laughs]

I think it’s good that he’s developing critical analysis at such a young age, especially with music, because music can be broken down in many ways.

It’s always up to interpretation isn’t it? And my son loves Onefour. But again, I just make sure we always have open conversations about lyrics. Especially with Onefour, I try to tell him that they’re wordplaying on something, or if they’re sounding violent, you know, it’s because of this, or it’s because of their environment. It’s important to break it down, and have open conversations about it.

Yeah, for sure. And he probably identifies with those guys because they’re Pacific Islanders.

That especially. He’s been around them a long time, they’re always nice to him, and it’s definitely as if looking up to them as older cousins. And that’s why the whole community looked at them, it broke down a lot of those doors and put batteries in a lot of people’s backs. Again, it goes back to representation. Being in the spaces that you are in, you want younger generations to see that.

Then I guess as someone who’s seen the growth and development of hip hop music, and hip hop culture in Australia over the decades, how can you describe the differences between the climate now and the climate that you came up in as part of Koolism?

It was a lot smaller. There wasn’t the internet how it is now, people didn’t utilise it like they did a few years later. It took you two hours to try and download a song. [laughs] It was a catch-22 because with the younger generation now, you really don’t have an excuse. You have resources and information at arm’s length. But the downside of that is, everyone has it. So there’s oversaturation. How do you cut through? On Spotify, 5000 songs get uploaded a day; you know, how do you cut through? Whereas with us, because the community was so small, it was easy to make our mark. But then, we didn’t have the same support as the artists have today. We were still looked at as a fad; we didn’t do many shows and didn’t have that much radio support. It wasn’t until Hilltop Hoods broke through, then everything opened up.

How did you manage a uniquely Australian Hip Hop sound?

Like everyone, we actually started rapping in American accents. But it wasn’t until I was actually thinking about it. Besides our stories, what makes us uniquely Australian? What’s going to make that difference? And then I heard groups from Melbourne, and the AKA Brothers, rapping in their actual accent. And I thought, wow, so you can do it and make it sound cool. So yeah, it just took a while to kind of adapt to that once it clicked. I was like, I can’t believe I wasn’t doing that before. And that made us uniquely Australian. Even though the music still was inspired by sounds from the UK or US, the voices were ours. And I always felt like that was going to set us apart from the US, UK, Europe, Asia. That’s what differentiates us.

And looking at hip hop now, it’s almost commonplace to rap in your Australian accent. Circling back to Onefour, you spent a lot of time with them, mentoring and guiding them. What was the biggest takeaway being a mentor for those guys?

I mean, they obviously learned a lot from me, but I learned a lot from them as well. And a lot of people say, “oh, you helped them with this, that” and it’s like, yeah, I did, but you have to give them credit, because they actually wanted to listen. That makes a big difference if people are open to what we’re saying, and are open to try it. That makes it so much easier. That’s why we have to give them a lot of credit for doing that. Because when we met they could have just looked at me, and thought, “What do you know?”. But they had faith. So, what I learned from that experience was regarding expectation. I had to realise you have to let people take their own journey in their own time, and find these things out on their own accord, because that’s how you really learn. If I said, do this, and then they did it, and nothing good came of it, they’re gonna turn around and wonder why they listened. Whereas if they made that decision and it didn’t work that way, then it would sit with them better than me trying to tell them. Expectation is a big thing.

Another endeavour of yours is Forever Ever Records, where you’ve got Becca Hatch and Hoodzy on your roster. Where do you see Forever Ever heading into the future?

What I set out to do was backing the artists I felt were unique. Especially after working with Onefour, that gave me the confidence to feel like I was right in thinking they would be somebody, because of gut instinct. But also, because they were so different to everyone at the time. So that’s what the label is about, backing people who want to make music on their own accord and be different. CG Fez, he’s very much a lyricist. He listens to people like Dave and wants to make music his way. And it may not get the numbers and the views of his peers, but that’s not what it’s about. It’s about art and expression, and doing it in a unique way. And that’s the same with Hoodzy and Becca. Hoodzy is kind of entering a phase now where she’s mixing punk with hip hop and dance. No one is really doing that. And that’s what excites me, that they’re thinking like this. It could be a longer road and may take a while for people to latch onto it, but that’s what builds longevity. Same as Becca, she comes from an R&B background, but now is playing with other kinds of subgenres like drum and bass, house, and disco. That’s what excites me, trying to push boundaries, and making something that’s culturally impactful. That’s what I want for Forever Ever.

I feel like you carry a big level of introspection in everything you do, and that plays out clearly in your book. What would you say has been your proudest moment in life so far?

I think my kids. Someone just told me that having kids is selfish. You want to have these other versions of yourself, and you look after them, you love them. I love my wife so much too, and we created these beautiful people. We look after them and raise them as best we can. And then they become their own selves. Then obviously, you’re still attached. But that next stage is on them where they want to go do what they want to do. That was who I dedicated my book to – children, past, present and future.

And then in talks of the future, where do you see yourself in a few years’ time?

Definitely still involved with music. But you know, a lot of things that have come up in the last couple of years, I never thought were ever in line, even being on radio. When I was wanting to be a rapper, I never thought that one day I’m gonna be on the radio. Then writing this book. It’s just a matter of working hard, and keeping your mind and eyes open to those opportunities. When Triple J came up, I was making music and I didn’t know whether to take it or not because of how I was gonna look as an artist. I was worried people were gonna look at me as just a radio host. But I took that opportunity and so many other opportunities came about. So yeah, the future is super bright. I’m looking forward to seeing my kids grow, and them having kids. I’m 46 now, and I think if you were to ask me 20 years ago, I definitely wouldn’t think I’d be doing what I’m doing now. Still being involved with music, still passionate about it. Still connected with like-minded people, it makes me think, man, the future’s bright. I’m excited.

KING: Life, Death & Hip Hop by Hau Latukefu & Christopher Riley is available now as a paperback, Ebook and audiobook — head here to grab your copy!