Vince Staples says he doesn’t give thought to most of the things I ask him, and it’s easy to understand why. Writers have spent an unhealthy amount of time covering his formative teen years as a Crip in Long Beach, and he’s acknowledged his whole family were members of the gang. His father spent a lot of time in and out of jail, both dealing and using drugs. His friends were getting incarcerated and killed since he was in his early teens. Why would he give a shit about another interview?

For Staples, rap is his 9-to-5 and the label is his boss. There are quotas to be met and journalists to be endured. He’s not alone in that thinking; it’s just that most rappers aren’t quite as frank about it. There are always going to be parts of a job you hate, but Staples doesn’t take the absurdity of the whole situation for granted.

“I’m able to take care of my family without a completed education and a criminal record, so I’m very, very happy about all the parts of it,” Staples tells me over the phone as he speeds along a Californian freeway. A lot of rappers talk about how making something of themselves in the game was all they ever aspired to, but that was never his goal. “Even if it is a dream for someone it’s still a job,” Staples says. “You have obligations based on this being your job, so that comes in giving people what they pay for, and showing up on time, and being respectful to the people who support the music.”

As the youngest child in a poor family in North Long Beach, rapping wasn’t something that even crossed Staples’ mind while growing up. It was during a visit to L.A., at the behest of close friend Dijon SAMO, that he made a vague connection to the then-incubating Odd Future. He became tight with Syd, who would often let him crash on her couch. Staples started making songs with the crew just so people would leave him in peace—and eventually he got really fucking good at it. His star turn on Earl Sweatshirt’s problematic (but since disavowed) ‘epaR’ set things off, and he moved on to his first full project in 2011. Despite the fact that Staples hates a lot of what he was making back then, his next string of mixtape releases led No I.D.—Kanye West’s mentor and Jay-Z’s 4:44 confidant—to sign him to Def Jam. The deal offered Staples the step up he needed to take his rightful place as one of the most innovative rappers out right now. These days he spends a significant chunk of his time performing for a rabid legion of fans all over the world.

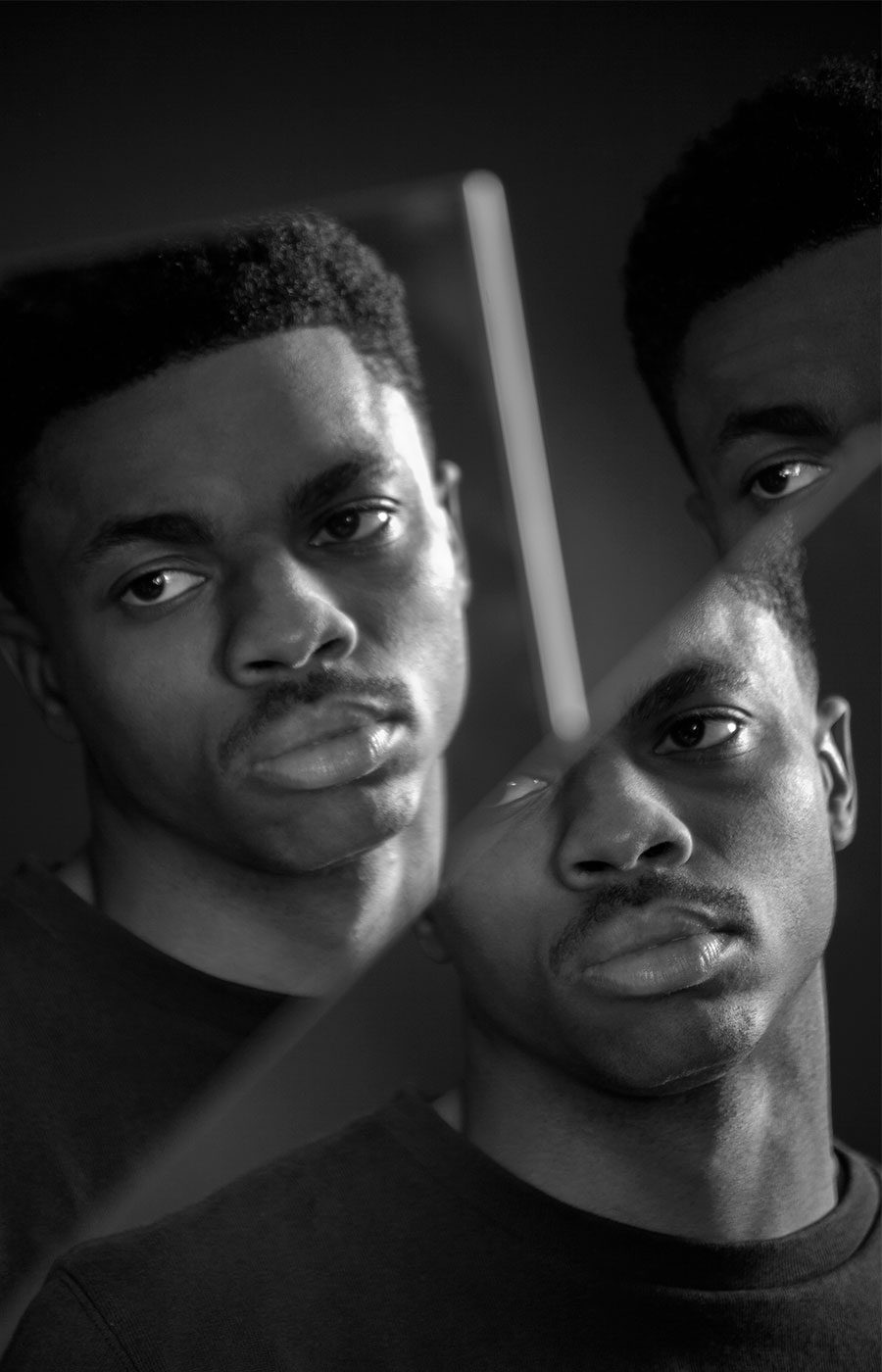

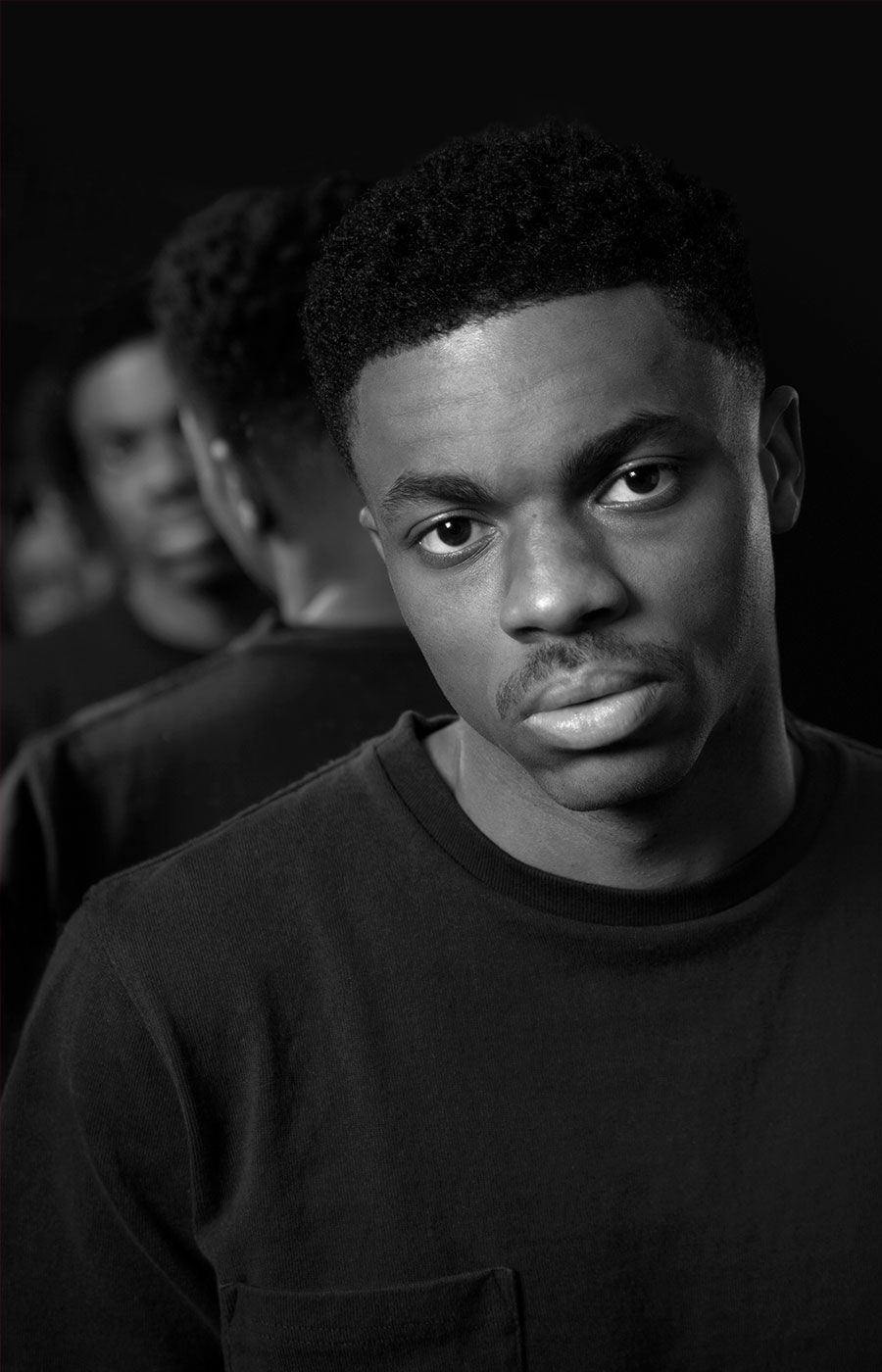

That’s what brings him to our studio in Australia for a photo shoot. When I first meet Staples he arrives decked out in all black. He moves through the room efficiently, shaking each person’s hand without really locking eyes with them. You have to wonder how many times he has to go through this exact routine every day with people he’ll probably never see again. While on set I make some awkward small talk with him about the corny stuff that rappers will often be set up to do in this country, citing the many times we’ve seen them in our social feeds standing mostly nonplussed next to a kangaroo or a koala. As he steps in front of the camera and is swamped by the crew, Staples tells me it’s invasive to get up close to animals like that.

In the past Staples has said that he sees “urban music” as a zoo, with most of its listeners sitting outside the cage. It’s a sentiment he’d play out in the visuals for ‘Senorita’ from his 2015 project Summertime ’06. In the music video he walks through a dilapidated, dystopian hood scene before it’s revealed that the entirety of this world is behind glass, and a Pleasantville-looking white family is gleefully observing the chaos. The theme still runs through his merchandise and even his new Converse line, which all prominently feature and are promoted with the phrase “don’t tap the glass”.

Staples’ zoo analogy is only further validated by the fact that he has recently felt better known for interviews than his music. For publications dealing in the currency of headlines and little else, an artist who speaks his mind as freely as Staples is a godsend. When we talk I refer to his quotes from previous articles and he laughs to himself a number of times before he responds. “I do a lot of these, if you haven’t noticed, so I don’t remember when or where I say any of this shit.”

“I say a lot of shit and I don’t know what it means,” he continues. “But I’m pretty sure I meant something.” It makes you question whether anything he says on record is actually true, and how much trolling and deflection has informed the current canon of his career. So what does he actually feel like he gets out of his communication with the media? “Nothing,” he says firmly. “Nothing at all.”

When I suggest he seems to have figured out it’s a two-way street and that speaking to these outlets gives him a further opportunity to get the message of the music out, he shuts that down too. “There’s not been one occurrence when I was like ‘let’s talk to someone’—they ask us, so we don’t need that,” he says. In fact, publications might have to look elsewhere for their next set of hot takes: “I feel like that’s demeaning to the message and the music, to have to try to speak your way into what you create,” he says. “I would rather my music not be successful than be secondary to some bullshit.”

It’d be a shame for an artist so naturally talented to have his music be the thing that fades into the background—especially when Staples seems to be at the peak of his powers. The release of 2017’s Big Fish Theory saw a significant shift: the heavy, down-tempo trap-inflected production of the Summertime ‘06 era went missing in action. While there were hints on intermediate project Prima Donna, no one could foresee Staples’ upgrade to the steely, automaton funk we’d get on his latest album.

Of course, the new sound has its detractors. Staples’ recent tongue-in-cheek attempt to raise $2 million using GoFundMe asked critics either to leave him alone, or fund his lifestyle and force him to “shut the fuck up forever”. The companion video to the campaign implies the fundraiser, and the release of his subsequent single ‘Get The Fuck Off My Dick’, was spurred on by frequent criticism of both his live performances and the “robot video game beats” he’s been rapping over most recently.

More than half a year on from the release of Big Fish Theory, and noting that Staples has a tendency to trash his older material, I ask whether the album was something he still feels proud of. “I feel like it’s good,” he offers humbly. “I mean, I was 15 when I was making music that I don’t particularly like. I think it’s only common sense to feel like you could have done better,” he explains. While fans of his earlier work might have been shocked when Staples switched the style up, they really should have known that we’d get here eventually. “I don’t have two projects that sound similar at all,” he says with conviction. “We don’t have to paint the same painting twice.”

His openness to experimentation seems to come from an understanding that all of the errors and missteps are just a natural part of the process. “I’m not really someone that’s afraid to make mistakes; that’s not really a fear of mine,” Staples says confidently. For him, it’s much more of a limiting factor to never know or accept where you went wrong. When I commend Staples for being a rapper who seems to be quite accepting of his own flaws in the public eye, he argues he’s not alone: “I think a lot of people do that; honestly, it’s been happening since DMX,” he says. While the Yonkers rapper is perhaps more known for his vividly aggressive content, DMX’s more self-reflective tracks, like ‘Slippin’’, illustrate what Staples is talking about. “Biz Markie’s got a song about being insecure about women, and everyone loves it,” he notes, alluding to 1989’s ‘Just A Friend’.

He names Future, 21 Savage, Logic, and Kendrick Lamar as others who have opened up about their own personal shortcomings. “A lot of people speak on their imperfection, the issues that they have in life, especially coming from what they like to call a street perspective,” Staples says. He believes that even flashes of this self-awareness deserve to be recognised, regardless of where they show up. “If you have a positive song, but 10 seconds of that are dedicated to what we’re speaking about; that doesn’t mean that it’s not present,” he says.

The focus for Staples so far has always been the fans—in his own terse way, of course. During his Australian shows Staples stands on the stage in front of an orange backdrop, a lone figure illuminated by white and yellow beams of light. No sign of a crew, no hypeman, not even an onstage DJ. Just Vince Staples. From my vantage point, he’s a singular shadow guarded by an endless sea of arms. He’s not here for the fake shit that other artists will often put forward at their shows. He won’t tell the crowd that they’re the craziest of the tour or pander to them at all. Occasionally, he’ll ask them whether they’re ready to have a good time. When he does his tone is detached and unemotional—but that’s just Staples.

The fans whose criticism helped birth his GoFundMe campaign are nowhere to be found in this crowd. In fact, the more he pulls back, the closer they draw in. A few times, he crouches in the middle of the stage, bordering on balled-up, rocking his head side to side rhythmically with the thumping electronica. In other moments, he simply stops engaging in repeating the chorus and stands back, allowing the fans to fill in the gaps—and they do so, loudly. While the crowd appears restless when Staples slows down the set, performing ‘745’ under a spotlight, ‘Blue Suede’ brings the energy rushing right back, before everything is cut to an abrupt close following the dizzying high of the anthemic ‘Norf Norf’. “I had a great time tonight,” he says. He doesn’t sound convincing, but the rest of the show was so bullshit-free that I want to believe the sentiment is real.

When I ask Staples about the most meaningful interactions he’s had with fans, his answer is surprisingly considered. “I don’t really weigh them against each other,” he says. “If anybody wakes up and decides to listen to your music or supports you, I appreciate ’em all equally. It’s about people’s time and money at the end of the day. They don’t have to give either one of those—I appreciate it regardless.” Even in the wake of fans calling him out for the product he’s providing, Staples has always been genuinely grateful for the opportunity that he’s been given by these people. While he won’t outwardly admit to making an attempt to leave his mark on each of them, he’s still aware of the power he wields. “I don’t really go into it much trying to change lives, or things like that. As I got older I understand the importance of what you say and what you do and how it affects other people.”

You would expect Staples to be uncomfortable with the idea of being a role model, but he knows that’s just one of the obligations he was talking about earlier. “You kind of ask for that when you take on this job,” he says. He takes it seriously, but he’s also just a man and feels like his fans understand that, “No one’s perfect, you just try to do the best you can—one thing about kids is that they accept you regardless.” I’ve seen that in the crowds, but it’s a far reach from Long Beach to Melbourne, and it’s impressive that his music is resonating so deeply with fans so far removed from his own experiences and upbringing. “That’s kind of the point of making the songs, is to tell your story to the rest of the world,” Staples says. “You have to share the insight with the people because that’s how we get closer to one another.”

While he’s mostly evasive when I raise anything about the current state of the world, I’ve noticed that Staples often talks about wanting to have children someday. I’m honestly surprised he’d be so open and forthcoming about this with a group of people who have often approached him in a fairly exploitative fashion. When I ask him what kind of world he hopes he can bring those kids into, he still doesn’t give me too much. “I don’t know; just a better one, as anyone would say,” he shrugs. When I go further and ask what he’s doing to make sure of that, it’s perhaps the first time I’ve heard him caught off guard. “I don’t know, man, that’s a good question,” he says. Staples is an incredibly fast talker, and it’s jarring to hear him take a pause this long. “That’s actually a very good question,” he reiterates. “But I’m working on it. Just trying to be a better person myself, I guess.”

Staples might not care much about what the media has asked of him but he’s investing himself in the things that matter—his family and friends, his diehard fans, his community, and his music. I know he’s no richer from our interaction, but when I thank him for his time he’s still more gracious than most of the artists I’ve interviewed, “No problem man, I appreciate you,” he says. It’s another hint that beyond the reluctance to admit the difference he’s making, the insistence that it’s all part of the job, and the ornery attitude, there’s a lot more to the man than he’s willing to let on.

After all of this I still can’t tell you who Vince Staples really is. And while he’s never been afraid to say what’s on his mind, I doubt he’ll ever tell you either. The reality is that we’re standing on this side of the glass—we don’t need to know it all.

This feature is taken from Acclaim Magazine issue 38, the Amplify issue, available here.

- Photography by: Mike Danischewski

- Styling by: Abby Bennett

- Make-up by: Colette Miller

- Grooming by: Jordan Mckenny